Thursday 22nd January 2026

It’s been a long time coming, but just before Christmas, the DfT published the final report evaluating the effectiveness of its £19.4 million Rural Mobility Fund.

That Fund, launched in March 2021, spearheaded 19 DRT schemes in 15 Local Authority areas across England each funded for a two to four year period and many of which have subsequently continued with Bus Service Improvement Plan funds. An Interim Report was published in October 2023 but by then only seven schemes had got going and some of those were still in their infancy leading to fascinating results including Essex’s DigiGo scheme carrying the grand total of 0.14 passengers per hour.

This Final Report, dated September 2025, covers all 18 of the 19 intended schemes with one, in Cumberland and Westmoreland & Furness, yet to start. It’s been compiled by a consortium holding a contract for the DfT for “Provision of Evaluation Research Support for Local and Regional Transport Analysis” which includes the University of Westminster and University of the West of England and provides an extensive review of each scheme. Despite the length of time that’s elapsed the analysis is based on data only up to September 2024. Nevertheless it paints an interesting picture of how DRT performs after a much more scientific and objective analysis than my sporadic random journey experiences over the last few years can ever achieve.

This Final Report is described as phase 1 with a phase 2 promised as a follow up which “is being conducted separately and will undertake impact and value for money evaluation to supplement the findings of phase 1 with a more in-depth assessment of the outcomes and impacts of the pilot schemes.”

There’s a myriad of tables and graphs in the Report with the most relevant setting out numbers of passengers using each service, revenue, and utilisation of vehicles, especially as in many cases these results are after two, three or more years operation, although the Report does make the point numbers are improving over that time in a number of cases while others have levelled off.

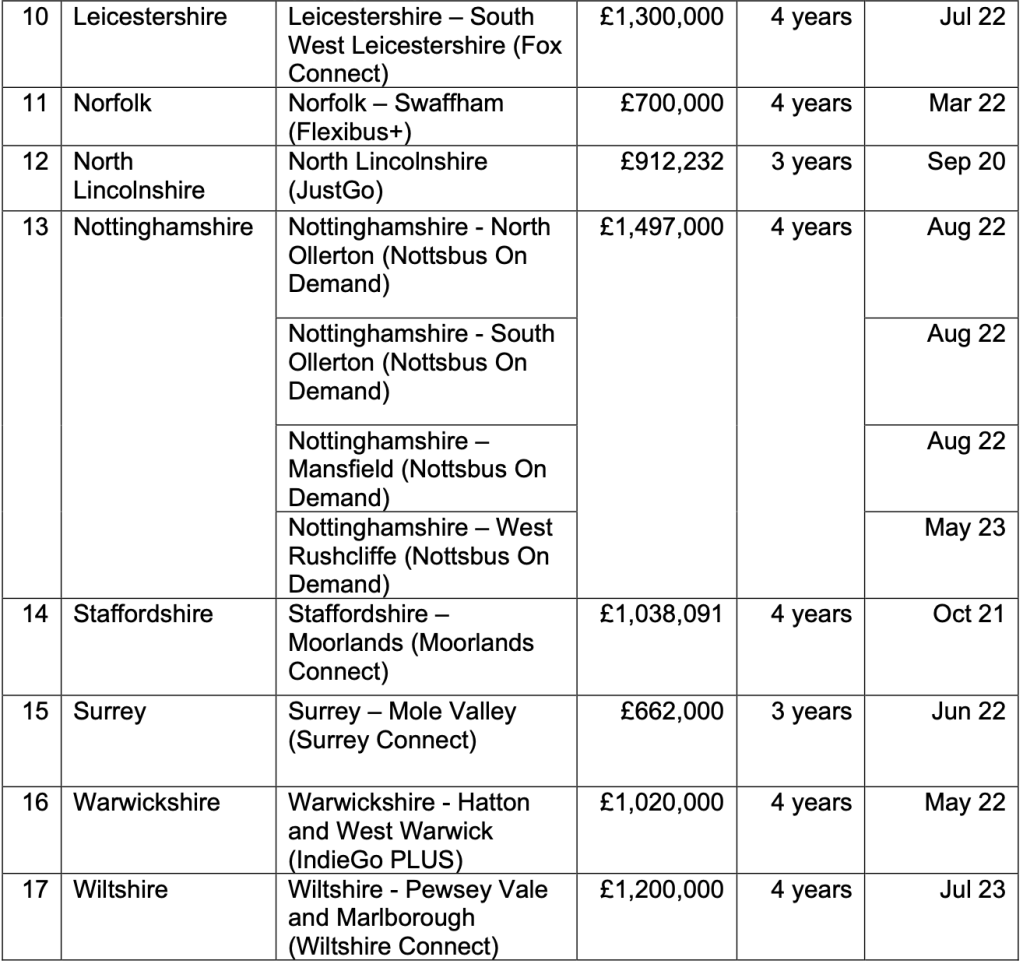

There’s a wide variety of schemes analysed ranging in geographic size from four square miles (Mansfield) to 337 square miles (North Lincolnshire); from schemes involving one minibus (North Cotswolds and Swaffham, Norfolk) to others involving six (High Wycombe and north west of Chelmsford). Altogether 55 minibuses have been involved. Interestingly the average percentage of journeys made with concessionary fares across the 18 schemes was the same (26%) as for local bus services in English non-metropolitan areas.

Overall, 87% of journeys were booked using mobile apps with phone bookings on 11% and the small balance on websites.

Ignoring North Lincolnshire which was an outlier, the average advance booking time was 2.7 days with longer lead times typically associated with concessionary fare journeys and phone bookings indicating an important user base of the services being less happy using technology to book their travel.

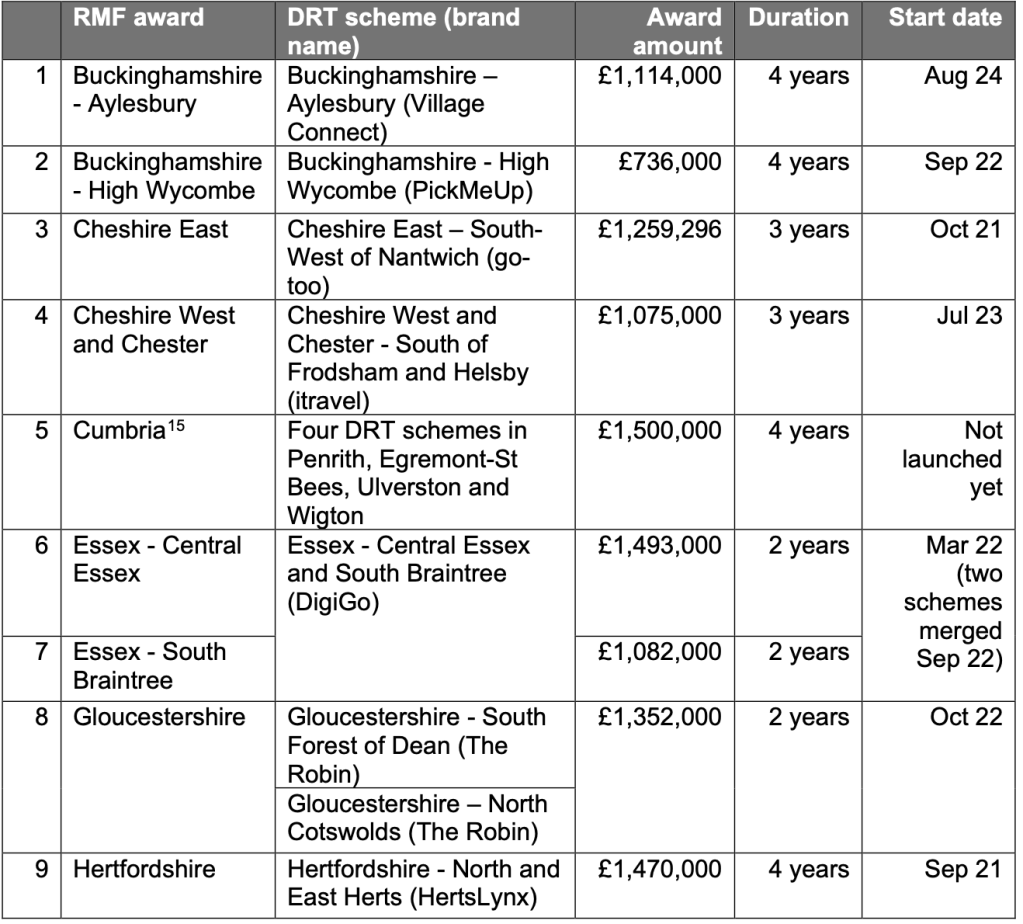

Here’s a summary of the 19 schemes, with their Rural Mobility Award amount, duration and start date.

After that preamble, here are the results.

Passengers

The most used scheme of the 18 is Buckinghamshire’s PickMeUp in High Wycombe with 3.9 passenger journeys per vehicle hour for the latest reporting period (six months to September 2024) with the Staffordshire scheme in the rural area north of Ashbourne the least used at 0.9 passengers per hour. Nine schemes managed between one and two passenger journeys per hour with five between two and three, and three (Cheshire West and Chester, Nottinghamshire’s West Rushcliffe and Wiltshire) achieving between three and three and a half passengers per hour.

Revenue

Revenue per passenger is slightly complicated by eight schemes being within the £2 fare cap and others not. For the whole Rural Mobility Fund period up to September 2024 total revenue from 823,490 passengers was £1,654,530 representing £2.01 per journey. The Report makes the point “if the £2 fare cap was not in place, fares would have been higher, which could increase revenue per journey, but may have reduced the number of journeys taken.”

Unfortunately the Report doesn’t include any information about operating costs for the schemes, which is a rather unfortunate omission, which in my judgement makes for a somewhat incomplete evaluation. Perhaps that will follow in phase two when value for money is considered, but for now, if we divide the £19.4 million Rural Mobility Fund by the 823,490 passengers who travelled up to September 2024 it gives a subsidy of £23.55 per passenger journey.

Vehicle utilisation

One of the challenges of DRT schemes is to minimise empty running between passengers being dropped off and wherever the next pick up is located. This is particularly pertinent to schemes across a wide geographic area. The Report sets out an “empty running ratio” for each scheme ranging from 0.45 to 1.09 with a mean value of 0.77 indicating 77 miles are driven empty for every 100 miles with a passenger on board. Four schemes (Essex, Norfolk and Nottinghamshire’s Mansfield and West Rushcliffe) have ratios of 1.0 or higher indicating more miles are run without passengers than with passengers. The 0.45 lowest ratio was achieved by Hertfordshire and Warwickshire with Leicestershire just above on 0.52 and North Lincolnshire on 0.57 which isn’t bad as it’s also the largest geographical area covered.

Unfulfilled bookings

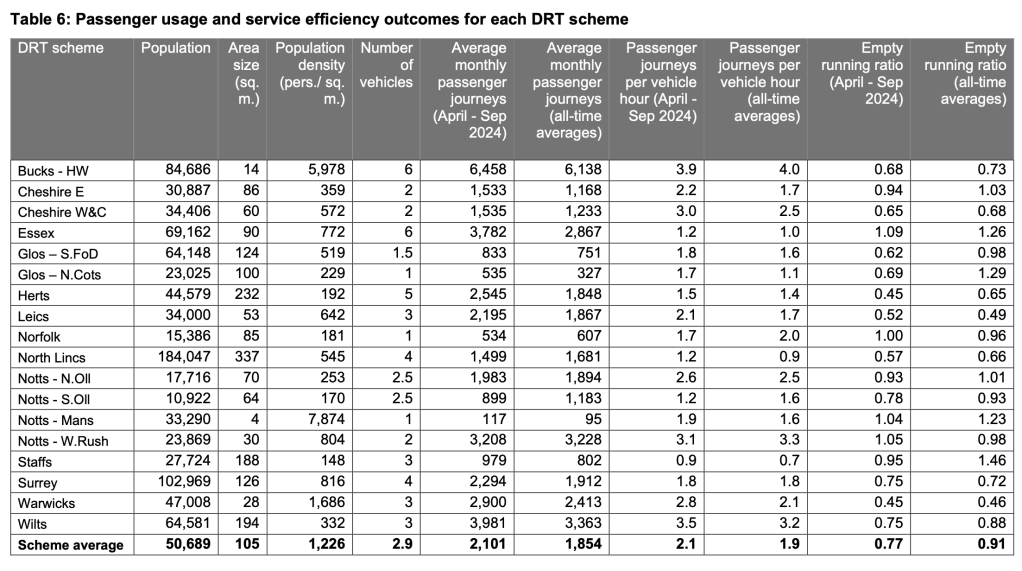

Another key metric, and one I’ve found personally exasperating over the years, is what’s called “unfulfilled bookings” – both passengers being unable to book a journey to meet their travel needs (as a bus isn’t available) and booked passengers failing to turn up for the journey. The Report notes “the relative number of unfulfilled bookings compared to fulfilled bookings is an indicator of the capacity of the DRT service to meet demand and of the service experience of users”. Local Authorities were asked to give a breakdown of unfulfilled bookings by reason but it proved challenging to collect such data due to it being held in different ways across different technology platforms.

Notwithstanding that limitation, the Report includes a ratio of unfulfilled bookings to fulfilled bookings across the schemes – a low ratio indicated a higher proportion of bookings being fulfilled, a high ratio indicates a high proportion being unfulfilled. For the latest data collection period (six months to September 2024) Surrey tops the unfulfilled chart with a ratio around 2.2 (the Report doesn’t give precise results and only displays them in a chart) indicating for every journey successfully made, more than double that number were unable to be accommodated and passengers left frustrated. The data shows in Surrey’s case 82% of the 31,140 unfulfilled bookings were for no service or vehicle being available, 15% the passenger cancelling and 3% cancelled by the provider. All in all a somewhat unsatisfactory state of affairs.

High Wycombe, Cheshire East, Cheshire West and Chester, Leicestershire, Staffordshire and Wiltshire all had ratios above 1.0 indicating more passengers turned away than being carried with Hertfordshire, and Nottinghamshire’s South Ollerton and West Rushcliffe between 0.5 and 1.0 and the other seven schemes between zero and 0.5.

Here are a couple of the Report’s tables giving more detail of passengers journeys per hour and empty running ratios for each scheme…

… and the ratio of unfulfilled to fulfilled bookings for both the latest reporting period (blue dots) and experience to date (red dots).

Among the Report’s conclusions are…

The Rural Mobility Fund (RMF) pilots have been perceived as successful by the Local Authorities (LAs). This is generally due to the pilots providing an enhanced level of public transport access in the areas they serve. For some LAs the pilot has also provided an opportunity to trial a transport solution that is new to them or would not be feasible without RMF funding. The pilots meant LAs were able to demonstrate to the public and local stakeholders what DRT is and how it can work in practice in their local areas.

….and, crucially ….

LAs and partners involved in the process evaluation felt that there are inherent tensions operationally between maximising revenue, maximising passenger numbers and maximising access to services. It was accepted that the numbers of passengers carried on DRT services in the pilot areas would be unlikely to cover operating costs from ticket income alone. Whilst the level of subsidy might vary between schemes, the aspiration in the longer term was to achieve at least equivalence with fixed route bus contracts.

My conclusion would be this Report shows very clearly that aspiration will always be elusive.

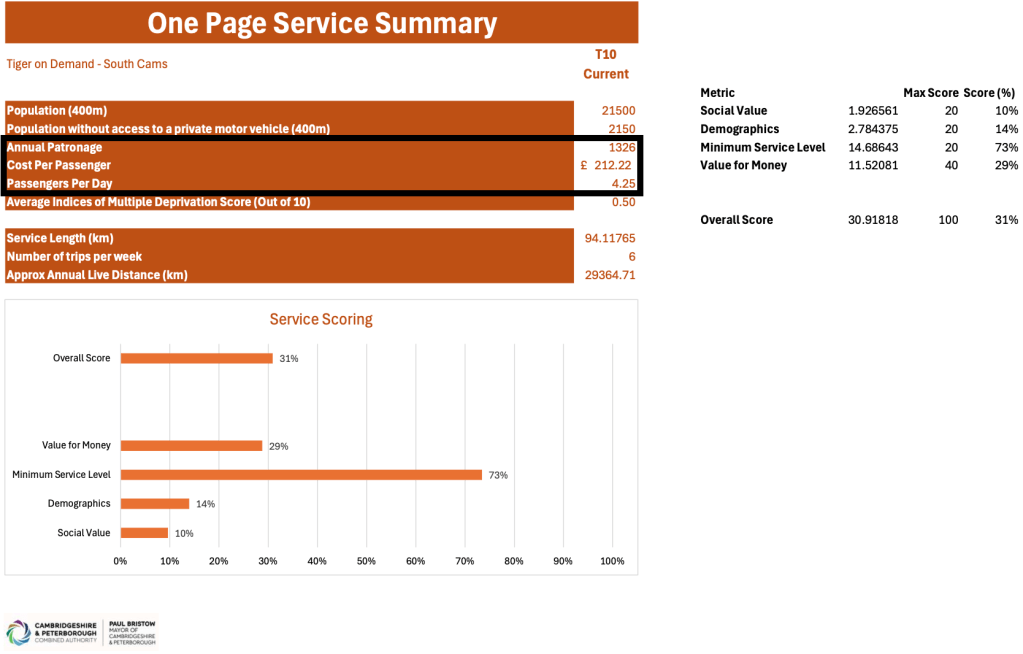

And for evidence of that, you need look no further than Cambridgeshire & Peterborough Combined Authority’s dalliance with its TigerOnDemand schemes set up with BSIP funding with the latest update provided to last week’s Transport Committee confirming the South Cambridgeshire T10 scheme…

… has a subsidy of £212.22 per passenger journey and sees only 4.25 passenger journeys per day.

Probably just two people travelling out and back, with an occasional third taking a ride.

Roger French

Blogging timetable: 06:00 TThS

Presumably the cost of this report – and its future instalment – are more money poured down the DRT drain. I wonder if a better use of it might have been to subsidise a few councillors in each case actually using the DRT services, talking to the drivers and any other users they chanced to come across, and reporting back to a council meeting

LikeLiked by 2 people

explain the t10, if that is two regulars are the destinations and times the same, could they be covered by a fixed route. Is it planned to check awareness in low use areas of service and readeons for not using it?

JBC Prestatyn

LikeLike

Sorry Surrey is interesting, with stats like that would indicate management action needed like look at lost journeys for desire paths and also success ones and map to existing network of fixed routes . O also recall the days of Peterbus which also had varied take up with some frustrations in that. Did Mole Valley coaches cover the area in the past, I think they used Karrjer welfare type buses on three fixed routes in North East Surrey.

JBC Prestatyn

LikeLike

is it time to review the transport excluded wider fir provision. London and I think Leeds have dial a ride for disabled to access social or trips to work, but the general public are excluded in part due to comprehensive other public transport. Now if we merge say in Cambridgeshire a dial a ride based on disabled users anywhere in the county with anyone in an origination or destination to somewhere in excess of 1km safe walking to a regular transport route

JBC Prestatyn

LikeLike

The closest I ever got to using a DRT service was Rutland’s ‘callconnect’, but it turns out that this doesn’t operate on Sundays (the only day when there are also no regular buses available). If it is just a subsidised taxi service, it would make sense to offer it at least at times when people are forced to use taxis due to the lack of alternative public transport.

LikeLike

It would be interesting to see an analysis of the effectiveness of the allocation software. Are they all using exactly the same principles for trip allocation? Do they involve any feedback or dialogue? By the latter I mean contacting the bookers, both those already accepted and potential ones to see if there’s flexibility in their trip requirements (time and destination).

Outside of that, is there any evidence of groups of passengers cooperating to simply make it possible for more to travel on the DRT?

Are there local DRT Users’ clubs?

For the whole concept to maximise effectiveness it strikes me that a high level of user participation in its day to day runner Ng is essential.

Treating DRT simply as an independent taxi service with minimal resources seems to me to be a recipe for guaranteed failure.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m replying to myself here as more and more thoughts arise. Given that the average pre-booking period is 2 days or more, there’s great scope for the operator to make publicly available the journeys that are already fixed for the next few days.

If potential short notice passengers could actually see what the bus will be doing on a particular day, and to see how many seats are available, then they might be able to fit in with that. A bit like a scheduled bus service but with a varying (but publicly visible) timetable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting blog, as ever, thanks Roger. One metric I’d be very interested in, but one which I doubt any booking system is configured to record, is the number of cases where a passenger was carried on their outward journey but then left stranded when unable to book the return trip later that day. Do such stats exist? It seems to me that the possibility of stranded is one of the significant reasons that undermine confidence in DRT schemes.

Richard Delahoy, Southend on Sea (where there are no DRT schemes, thankfully)

LikeLiked by 1 person

My observation is that this report looks at the operation of DRT from a Council’s perspective, rather than from a users persoective. Did the report ask users for their views, why did they travel, what did they do before DRT was introduced, did it meet their needs, would they use it again etc etc

MotCO

LikeLike

The report focuses on the costs but in the form presented on this blog doesn’t appear to comment on the social benefit. Having used the Nottinghamshire scheme and talking with passengers it’s clear that the service is invaluable to them. For Nottinghamshire, DRT is just one of the pieces in a county-wide public transport provision. Passengers commented that using a ‘normal’ bus offers them a level of dignity that the erstwhile social services-adapted minibuses didn’t offer. It’s easy to criticise DRT in terms of cost per person, but the benefit to that person shouldn’t be overlooked. Of course, a private taxi might do the job just as well, but then that negates the county council’s wish to provide public transport options for as wide a cohort as possible.

LikeLike

In Dorset we have DCT’s “PlusBus” which seems to be well used and cost-effective by virtue of being to fixed destinations (ie a town with shops) on certain days only. You need to pre-register and pick ups are within a designated (rural) area. DCT says: “We do not receive any direct subsidy for our PlusBus service – we provide it as part of our charitable objectives and public benefit to help improve transport opportunities to individuals within the community. Dorset Council supports the service by enabling the use of National Bus Passes and project funding to improve services and trial new routes.” – Tony Smale

LikeLike

As always a useful bit of analysis of a report that is focused on providers rather than users.

One thing not mentioned is whether the DRT schemes were additions to the network or are replacements for withdrawn local bus contracts. Here in Notts the schemes that replaced fixed routes (N Ollerton, S Ollerton, W Rushcliffe) appear to provide a good service. However, the Mansfield evening scheme was an addition – there having been no evening buses in the areas covered for sometime.

As always though, the failure of the Mansfield evening scheme is largely because of a depressed local economy meaning no demand. The majority only travel for a reason, no reason no travel. Unless someone revives the evening economy the buses will remain empty.

Richard Warwick

LikeLike